This parasite caught my attention because it is extremely important in Micronesia, yet practically unknown to physicians who work in the islands.

In Chuuk (formerly known as Truk), Alicata described infection with this severe parasite from eating raw African Giant Snails, as well as eating raw shrimp. On Guam, a dish known as Shrimp Kelaguen is highly valued at fiestas and parties. Raw shrimp, Macrobrachium sp., are squeezed into the mix. This, the Rat Lungworm, is transmitted by the shrimp and the snail as intermediate hosts. In humans, who are not part of the natural life cycle of the parasite, these worms cause Eosinophyllic Meningitis.

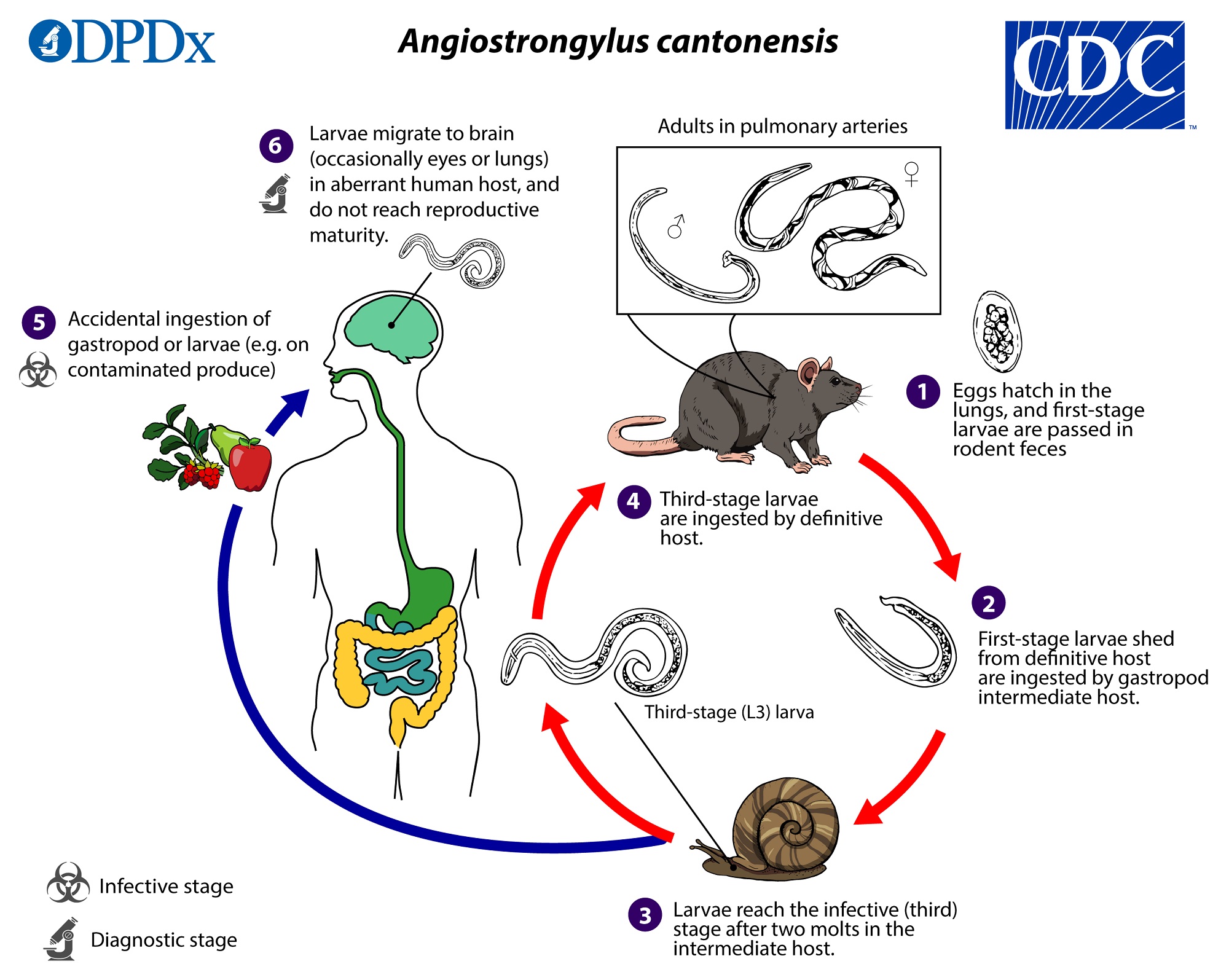

|

| The Life Cycle. |

Eosinophyllic Meningintis is a serious disease that is seldom diagnosed because it is difficult to detect. Physicians working in Chuuk, for example, when I interviewed them in 1987 or 1988, did not know about this worm. When I mentioned "Angiostrongylus cantonensis" to a physician at CHuuk Hospital who had a bachelor's degree in Parasitology, he thought I was referring to Strongyloides, the whip worm, a common intestinal disease in the islands. This physician was well trained, and deeply engaged in his work: he took the initiative of personally performing the microscopical observations of fecal samples for Ova and Parasites (O&P); yet he did not know this worm that is well documented in the islands.

|

| From Alicata 1991 with carriers. |

Elmer Noble was a co-author of the textbook for the Parasitology course I was enrolled in, at UCSB, in 1984. Dr. Noble visited our campus, where I think he previously had taught, and presented a guest lecture. He warned us that physicians he had met during his travels in Asia were not well trained concerning parasites. He often diagnosed persons whose parasitic infections had been overlooked in routine hospital exams, for example in Japan. So it is not unsurprizing that Angiostrongylus cantonensis is not well known in Micronesia; but this is especially concerning when a book and multiple research papers had been published on this issue by an expert in the field.

| |||

| From Alicata 1991 |