- I saw this ...

- I (heard) but did not see this ...

- I have seen evidence of this ...

- I got the information from someone else about this ...

- It is reasonable to assume that ...

From WikiPedia:

Again from Nettle and Romaine:

Some languages have a distinct grammatical category of evidentiality that is required to be expressed at all times. The elements in European languages indicating the information source are optional and usually do not indicate evidentiality as their primary function — thus they do not form a grammatical category. The obligatory elements of grammatical evidentiality systems may be translated into English, variously, as I hear that, I see that, I think that, as I hear, as I can see, as far as I understand, they say, it is said, it seems, it seems to me that, it looks like, it appears that, it turns out that, alleged, stated, allegedly, reportedly, obviously, etc.

Languages like Turkish, Kwakiutl, Navajo, and Hopi have different conjugations of the verb which distinguish heasay from what is the speaker's own knowledge.Nettle and Romaine quote the following by "a European explorer" about the languages of Rossel Island, Papua New Guinea.

Any that we heard were scarcely like human speech in sound, and were evidently very poor and restricted in expression. Noises like sneezes, snarls and the preliminary stages of choking---impossible to reproduce on paper---represented the names of villages, people, and things.

Does one need to explain the point of view expressed here?

Japanese in Micronesia implemented education of native peoples in the Japanese Language. My son's grandparents were proud of their knowledge of Japanese. The apparent prevailing point of view was that the natives, not being Japanese, could not be human, but by learning the Japanese language to some rudimentary level some level of humanity could be bestowed upon them.

Nettle and Romaine point out that the Aztec term Nahuatl, referring to their language means "pleasant sounding". The word "barbarian" derives from Greek barbarus, "one who babbles".

The point of evidentiality would be lost on many Americans in 2018. One would hope that globalization might engender not only tolerance, but mutual understanding and Love. Nettle and Romaine also emphasize the signficant similarities among European languages, a fact pressed upon me by learning two languages with only slight taint of colonizers' influence.

This book came to my view because of the discussion of fish names and marine lore among Pacific Islanders.

For further reflection.

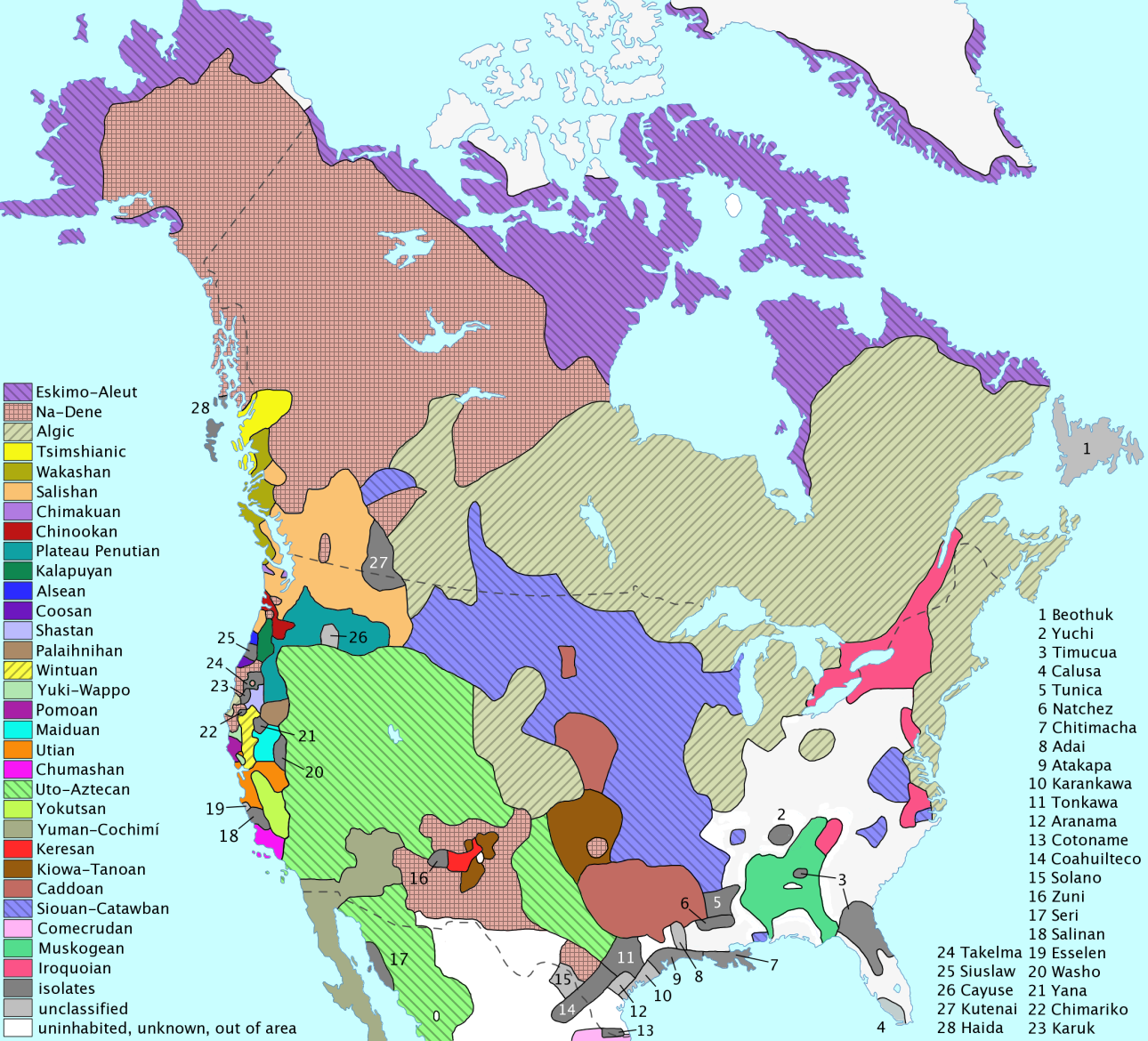

|

| North American languages at the time of colonization. |

This map on Wikimedia is incomplete:

From Wikipedia:

Chumashan (meaning "Santa Cruz Islander") is a family of languages that were spoken on the southern California coast by Native American Chumash people, from the Coastal plains and valleys of San Luis Obispo to Malibu, neighboring inland and Transverse Ranges valleys and canyons east to bordering the San Joaquin Valley, to three adjacent Channel Islands: San Miguel, Santa Rosa, and Santa Cruz.[2]The Chumashan languages may be, along with Yukian and perhaps languages of southern Baja such as Waikuri, one of the oldest language families established in California, before the arrival of speakers of Penutian, Uto-Aztecan, and perhaps even Hokan languages. Chumashan, Yukian, and southern Baja languages are spoken in areas with long-established populations of a distinct physical type. The population in the core Chumashan area has been stable for the past 10,000 years. However, the attested range of Chumashan is recent (within a couple thousand years). There is internal evidence that Obispeño replaced a Hokan language and that Island Chumash mixed with a language very different from Chumashan; the islands were not in contact with the mainland until the introduction of plank canoes in the first millennium AD.[3]

I was born and came of age in Chumash country. I was 20 years of age before I knowingly met a Chumash American. It was not under auspicious circumstances.

Corrected map of distribution of Chumash at colonization: